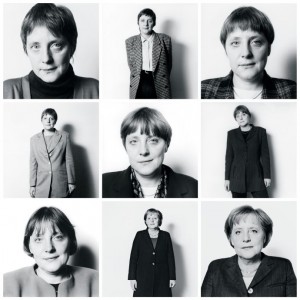

The Quiet German – a portrait of Angela Merkel

Very lucid, well-written story by Gorge Packer in the New Yorker about the German chancellor:

German politics was entering a new era. As the country became more “normal,” it no longer needed domineering father figures as leaders. “Merkel was lucky to live in a period when macho was in decline,” Ulrich said. “The men didn’t notice and she did. She didn’t have to fight them—it was an aikido politics.” Ulrich added, “If she knows anything, she knows her macho. She has them for her cereal.” Merkel’s physical haplessness, combined with her emotional opacity, made it hard for her rivals to recognize the threat she posed. “She’s very difficult to know, and that is a reason for her success,” the longtime political associate said. “It seems she is not from this world. Psychologically, she gives everybody the feeling of ‘I will take care of you.’ ”

…

“People say there’s no project, there’s no idea,” the senior official told me. “It’s just a zigzag of smart moves for nine years.” But, he added, “She would say that the times are not conducive to great visions.” Americans don’t like to think of our leaders as having no higher principles. We want at least a suggestion of the “vision thing”—George H. W. Bush’s derisive term, for which he was derided. But Germany remains so traumatized by the grand ideologies of its past that a politics of no ideas has a comforting allure.

…

Merkel and Obama:

…

In Obama’s first years in office, Merkel was frequently and unfavorably compared with him, and the criticism annoyed her. According to Stern, her favorite joke ends with Obama walking on water. “She does not really think Obama is a helpful partner,” Torsten Krauel, a senior writer for Die Welt, said. “She thinks he is a professor, a loner, unable to build coalitions.” Merkel’s relationship with Bush was much warmer than hers with Obama, the longtime political associate said. A demonstrative man like Bush sparks a response, whereas Obama and Merkel are like “two hit men in the same room. They don’t have to talk—both are quiet, both are killers.” For weeks in 2011 and 2012, amid American criticism of German policy during the euro-zone crisis, there was no contact between Merkel and Obama—she would ask for a conversation, but the phone call from the White House never came.

As she got to know Obama better, though, she came to appreciate more the ways in which they were alike—analytical, cautious, dry-humored, remote. Benjamin Rhodes, Obama’s deputy national-security adviser, told me that “the President thinks there’s not another leader he’s worked closer with than her.” He added, “They’re so different publicly, but they’re actually quite similar.” (Ulrich joked, “Obama is Merkel in a better suit.”) During the Ukraine crisis, the two have consulted frequently on the timing of announcements and been careful to keep the American and the European positions close. Obama is the antithesis of the swaggering leaders whom Merkel specializes in eating for breakfast. On a trip to Washington, she met with a number of senators, including the Republicans John McCain, of Arizona, and Jeff Sessions, of Alabama. She found them more preoccupied with the need to display toughness against America’s former Cold War adversary than with events in Ukraine themselves. (McCain called Merkel’s approach “milquetoast.”) To Merkel, Ukraine was a practical problem to be solved. This mirrored Obama’s view.

Read the article in the New Yorker